An index fund is a type of mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) engineered to replicate the performance of a specific market benchmark, such as the S&P 500 or the MSCI World index. Instead of employing a portfolio manager to actively select securities in an attempt to outperform the market, an index fund follows a passive investment strategy. It simply buys and holds the securities that constitute the index, matching their respective weights. This methodology provides investors with broad market exposure at a minimal cost.

The rise of index funds is one of the most significant developments in modern finance. It offers a transparent, low-cost, and systematically diversified approach to investing. For individuals seeking to build long-term wealth without engaging in complex security analysis, a clear, analytical understanding of how index funds operate is an essential first step.

The Principle of Passive Investing

The intellectual foundation for index funds is the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), a theory largely developed by Nobel laureate Eugene Fama. The EMH posits that asset prices fully reflect all available information. In a perfectly efficient market, consistently outperforming the market on a risk-adjusted basis through active stock picking would be impossible. While the degree of market efficiency is a subject of academic debate, empirical evidence overwhelmingly supports the practical challenges of active management.

Pioneered by John Bogle, who launched the first public index fund at Vanguard in 1976, passive investing has gained widespread acceptance. Decades of data have demonstrated that a significant majority of actively managed funds fail to beat their benchmark indices after accounting for their higher fees. According to a 2024 Morningstar report, nearly 90% of active U.S. large-cap funds underperformed their benchmarks over the preceding 10-year period. This performance gap has driven a massive shift of capital toward passive strategies, with over half of U.S. equity assets now held in passively managed funds.

Types of Index Funds

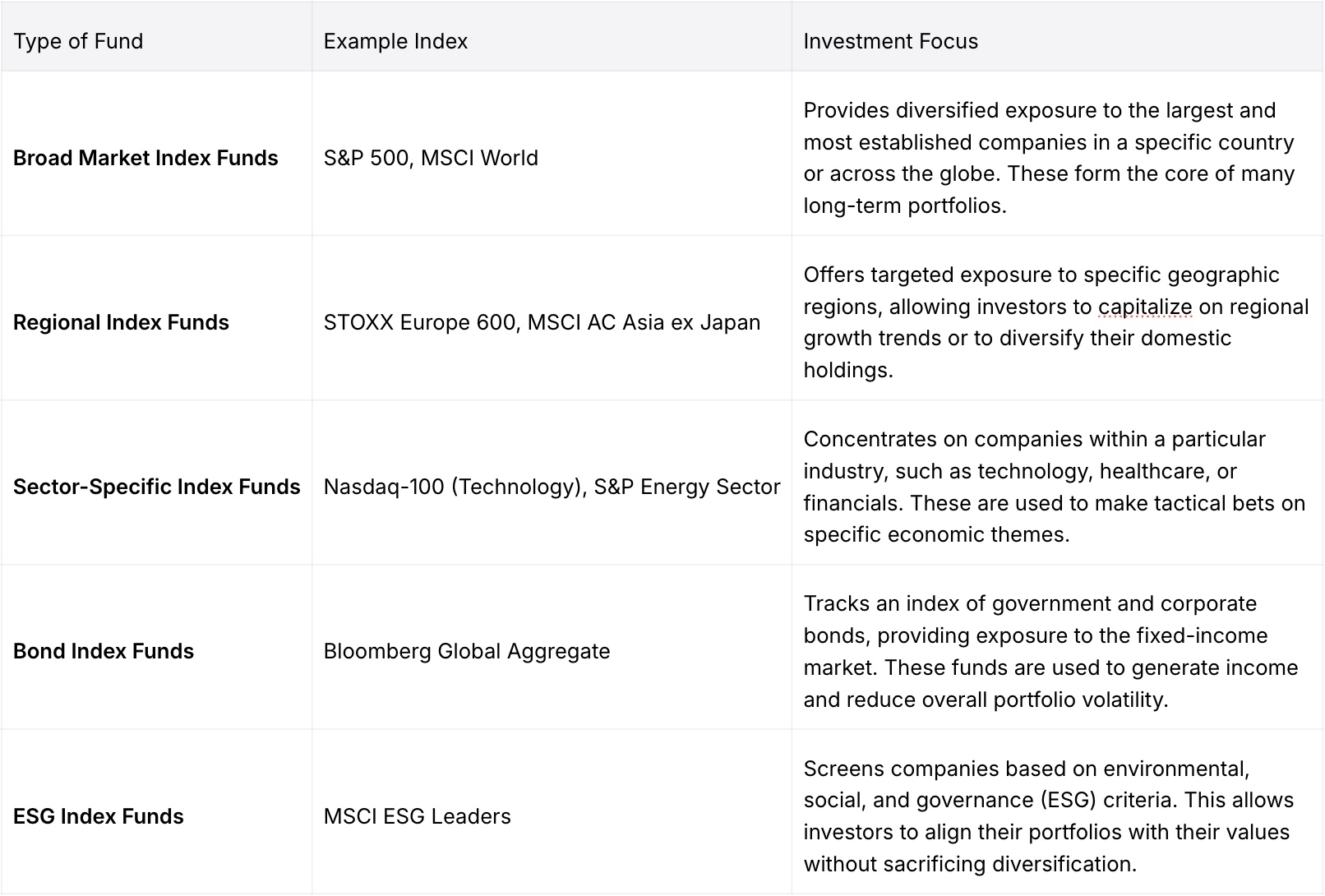

The index fund universe has expanded significantly, offering investors the ability to gain targeted exposure to virtually every corner of the global market. While the strategies are passive, the choices are vast. A structured understanding of the primary categories is crucial for effective portfolio construction.

Global Adoption and Key Benefits

The shift toward passive investing is a global phenomenon, driven by a compelling set of advantages that appeal to both individual and institutional investors. The analytical case for index funds rests on several key pillars that contribute to superior long-term, risk-adjusted returns for the average investor.

Low Cost

This is the most significant advantage of index funds. Because they do not require expensive teams of research analysts or active portfolio managers, their operational costs are minimal. The average expense ratio for an index fund is often around 0.10% or lower, compared to an average of closer to 1.00% for actively managed funds. This cost difference, compounded over decades, can have a substantial impact on an investor's final portfolio value.

Transparency

The holdings of an index fund are determined by the public, rules-based methodology of the index it tracks. This means an investor knows exactly what securities they own at all times. This transparency stands in contrast to some actively managed funds, where holdings may be less frequently disclosed and can change at the manager's discretion.

Consistent Performance

While an index fund will, by definition, never "beat" the market, it will also never significantly underperform it. It delivers the market's return, less its minimal fee. This consistency removes the risk of selecting an underperforming active manager—a risk that data shows is statistically high.

Diversification

A single share of a broad-market index fund can provide an investor with ownership in hundreds, or even thousands, of different companies. This instant diversification is a powerful tool for mitigating unsystematic risk—the risk associated with the poor performance of a single company.

Risks and Limitations to Consider

Despite their numerous benefits, index funds are not without risk. A balanced analysis requires an understanding of their inherent limitations.

- Market Risk: The primary risk of any index fund is systemic market risk. If the index the fund tracks declines in value, the fund's value will fall in lockstep. Indexing does not protect against broad market downturns.

- Tracking Error: In practice, an index fund's return may deviate slightly from the exact return of its benchmark index. This small discrepancy, known as tracking error, can arise from fees, transaction costs, and the fund's sampling methodology.

- Concentration Risk: Some market indices can become heavily concentrated in a few large companies or a single sector. For example, indices like the S&P 500 have a significant weighting in large technology stocks. An investor in such a fund may have more exposure to a specific sector than they realize.

Even with these considerations, the evidence strongly suggests that for the vast majority of investors, a disciplined, long-term strategy centered on low-cost index funds offers the most reliable path to building wealth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Are index funds a safe investment?

Index funds carry market risk, meaning their value will fluctuate with the broader market. However, they largely eliminate "manager risk"—the risk that a fund manager's poor decisions will lead to underperformance. Due to their high level of diversification, they are generally considered a safer way to invest in equities than picking individual stocks.

2. Should I choose an ETF or a mutual fund version of an index fund?

The primary difference is in their trading mechanism. ETFs (exchange-traded funds) trade like stocks throughout the day, while mutual funds are priced once per day after the market closes. For most long-term investors, this difference is minor. The choice often comes down to the specific fund's expense ratio and the investor's brokerage platform.

3. Why are the fees for index funds so low?

Their costs are minimal because the investment process is largely automated. Index funds do not need to pay for active portfolio managers, large research teams, or frequent trading. They simply follow a predetermined set of rules to mirror an index.