Hedging is a strategic financial maneuver designed to mitigate risk by taking an offsetting position in a related asset. In essence, it functions as a form of insurance for an investment portfolio. Businesses, institutional funds, and individual investors employ hedging techniques to limit their exposure to adverse fluctuations in prices, currency exchange rates, or interest rates. The primary tools for this practice are financial derivatives—such as options, futures, and swaps—which allow for the precise transfer of risk.

The core objective of hedging is not to generate profit but to protect against potential losses. It is a defensive strategy aimed at reducing volatility and creating more predictable financial outcomes. For any investor seeking to build a resilient portfolio, a clear, analytical understanding of hedging is indispensable. It represents the shift from pure speculation to sophisticated risk management, a cornerstone of modern financial theory and institutional practice.

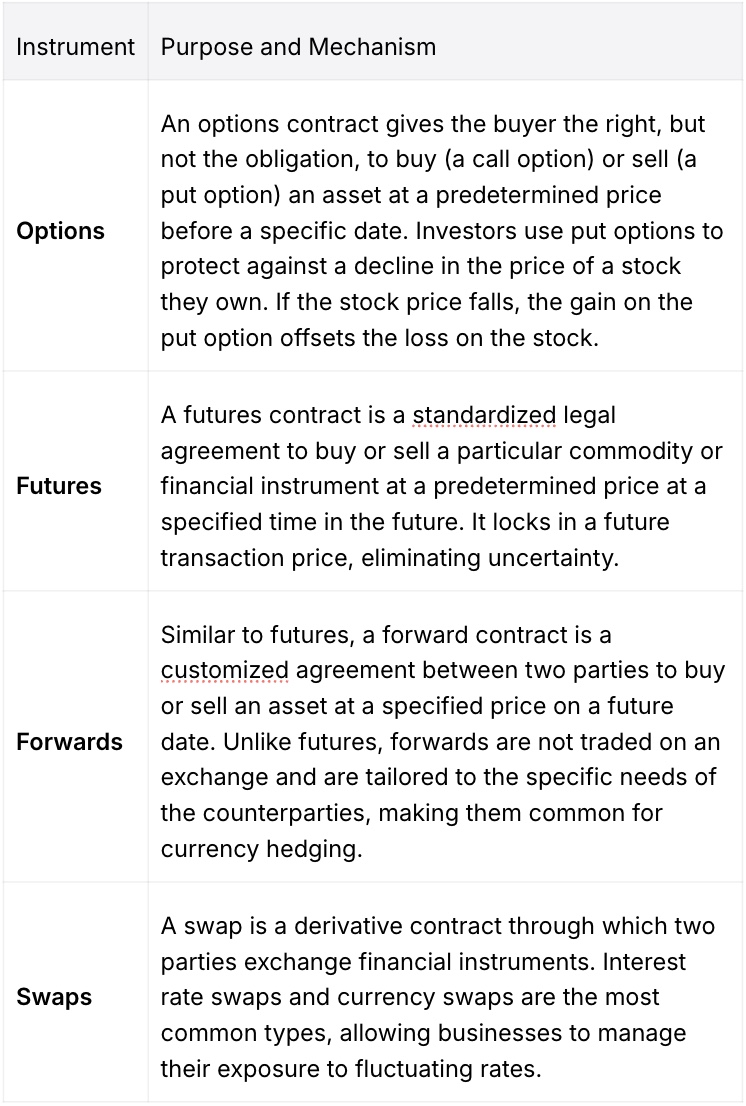

Common Hedging Instruments and Their Purpose

Hedging is executed using a variety of financial instruments, each designed to counteract a specific type of risk. The choice of instrument depends on the nature of the exposure, the time horizon, and the strategic objective of the hedge. A structured analysis of the primary tools reveals their distinct functions.

Real-World Applications of Hedging

The theoretical concept of hedging is best understood through its practical applications across different sectors of the economy. These examples demonstrate how hedging is used to stabilize cash flows and protect profits from market volatility.

Corporate Hedging

A multinational corporation with operations in both Europe and the United States faces currency risk. If a Swedish exporter generates revenue in U.S. dollars (USD) but its costs are in Swedish kronor (SEK), a depreciation of the USD against the SEK would erode its profit margins. To mitigate this risk, the company can enter into a forward contract to sell its expected USD revenues at a predetermined USD/SEK exchange rate, thereby locking in its future profits in SEK.

Similarly, an airline is heavily exposed to fluctuations in the price of jet fuel. A sudden spike in oil prices could decimate its profitability. To manage this, the airline can use oil futures contracts to lock in the price it will pay for fuel months in advance. If oil prices rise, the gain on the futures contracts will offset the higher cost of physical fuel, stabilizing its largest operational expense.

Portfolio Hedging

An investor with a large, diversified portfolio of U.S. stocks may become concerned about a potential market downturn. Instead of selling the stocks—which could trigger capital gains taxes and miss a potential rebound—the investor can purchase put options on a broad market index like the S&P 500. If the market falls, the value of the put options will increase, offsetting a portion of the portfolio's losses and cushioning the impact of the downturn.

The Benefits and Costs of Hedging

A balanced analysis of hedging requires weighing its significant benefits against its explicit and implicit costs. It is a strategic trade-off between risk reduction and potential return.

Key Benefits

- Reduced Volatility: The primary benefit is the smoothing of returns and cash flows. Hedging reduces the impact of adverse market movements, leading to more predictable financial outcomes.

- Profit Protection: By mitigating downside risk, hedging allows investors and businesses to protect accumulated gains from being erased by sudden market shocks.

- Cash Flow Stabilization: For corporations, hedging key input costs or foreign currency revenues provides greater certainty in financial planning and budgeting.

Costs and Limitations

- Direct Costs: Hedging is not free. Buying options requires paying a premium, which is a non-recoverable cost if the hedge is not needed. Using futures requires posting margin, which ties up capital.

- Limited Upside: The trade-off for reducing downside risk is often a limitation on upside potential. If an investor hedges a stock position and the stock price soars, the hedge may cap the potential gains. For example, some options strategies protect against losses but also limit profits above a certain price.

- Complexity and Basis Risk: Hedging can be complex to implement correctly. "Basis risk" occurs when the hedging instrument does not perfectly track the price of the asset being hedged, leading to an imperfect hedge that can still result in unexpected losses.

Strategic Considerations: Hedging vs. Speculation

It is analytically critical to distinguish hedging from speculation. The goal of a hedge is strictly risk reduction. It is a defensive move designed to neutralize an existing exposure. Speculation, by contrast, is the act of taking on risk in the hope of generating a profit. A speculator uses derivative instruments to bet on the future direction of a market, whereas a hedger uses them to protect against it.

Modern portfolio theory recognizes the value of effective hedging in constructing an optimal portfolio. Furthermore, regulatory frameworks like the Basel III accords, which govern bank capital requirements, acknowledge that properly executed hedges reduce the overall risk profile of financial institutions, contributing to greater stability in the financial system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Is hedging a strategy reserved only for large institutions and professionals?

No. While large institutions are the primary users of complex hedging strategies, the proliferation of financial products like exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and standardized options contracts has made basic hedging techniques accessible to individual investors.

2. Can an investor hedge against inflation?

Yes. Investors can hedge against inflation risk by allocating capital to assets whose value tends to rise with the general price level. These include Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), commodities, and real estate.

3. What is "over-hedging"?

Over-hedging occurs when the size of the hedge position exceeds the actual underlying exposure. This is a critical mistake that transforms a defensive hedge into a speculative bet. For example, if an investor owns 100 shares of a stock but buys put options to protect 200 shares, they have created a net short position that will lose money if the stock price rises.