Fixed income represents the bedrock of global capital markets. This asset class refers to investments that generate predictable returns, typically in the form of regular interest payments and the eventual repayment of the original principal at maturity. Governments, corporations, and municipalities issue fixed-income securities—commonly known as bonds—to raise capital for various purposes. In turn, investors utilize these securities to balance portfolio risk, preserve capital, and generate a stable stream of income.

Unlike equities, which signify ownership in a company, a fixed-income investment is fundamentally a loan. The investor lends money to an issuer, and in exchange, the issuer promises to pay a predetermined rate of interest over a specified period. This structural difference makes the asset class inherently less volatile than stocks. However, fixed-income securities are not without risk; their value is sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates, inflation, and the creditworthiness of the issuer. For any serious investor, a clear analytical understanding of this asset class is essential for constructing a resilient and diversified portfolio.

How Fixed-Income Securities Work

At its core, a fixed-income security is a contractual agreement between a lender (the investor) and a borrower (the issuer). When you purchase a bond, you are lending capital to the issuing entity. The terms of this loan are clearly defined and include the principal amount, the interest rate (or coupon), and the maturity date. The issuer agrees to make periodic interest payments—the coupon payments—and to return the full principal amount to the investor when the bond matures.

For example, if you were to invest $10,000 in a five-year corporate bond with a 3% annual yield, you would receive $300 in interest each year for five years. At the end of the term, the issuer would return your original $10,000 principal. This predictability is the primary appeal of fixed-income assets.

However, the market value of a bond is not static; it fluctuates in response to changes in prevailing interest rates. This creates an inverse relationship between bond prices and yields. When central banks raise interest rates, newly issued bonds offer higher yields, making existing bonds with lower coupons less attractive. As a result, the market price of older, lower-yielding bonds will decline. Conversely, when interest rates fall, existing bonds with higher coupons become more valuable, and their prices rise. This dynamic is central to fixed-income investing.

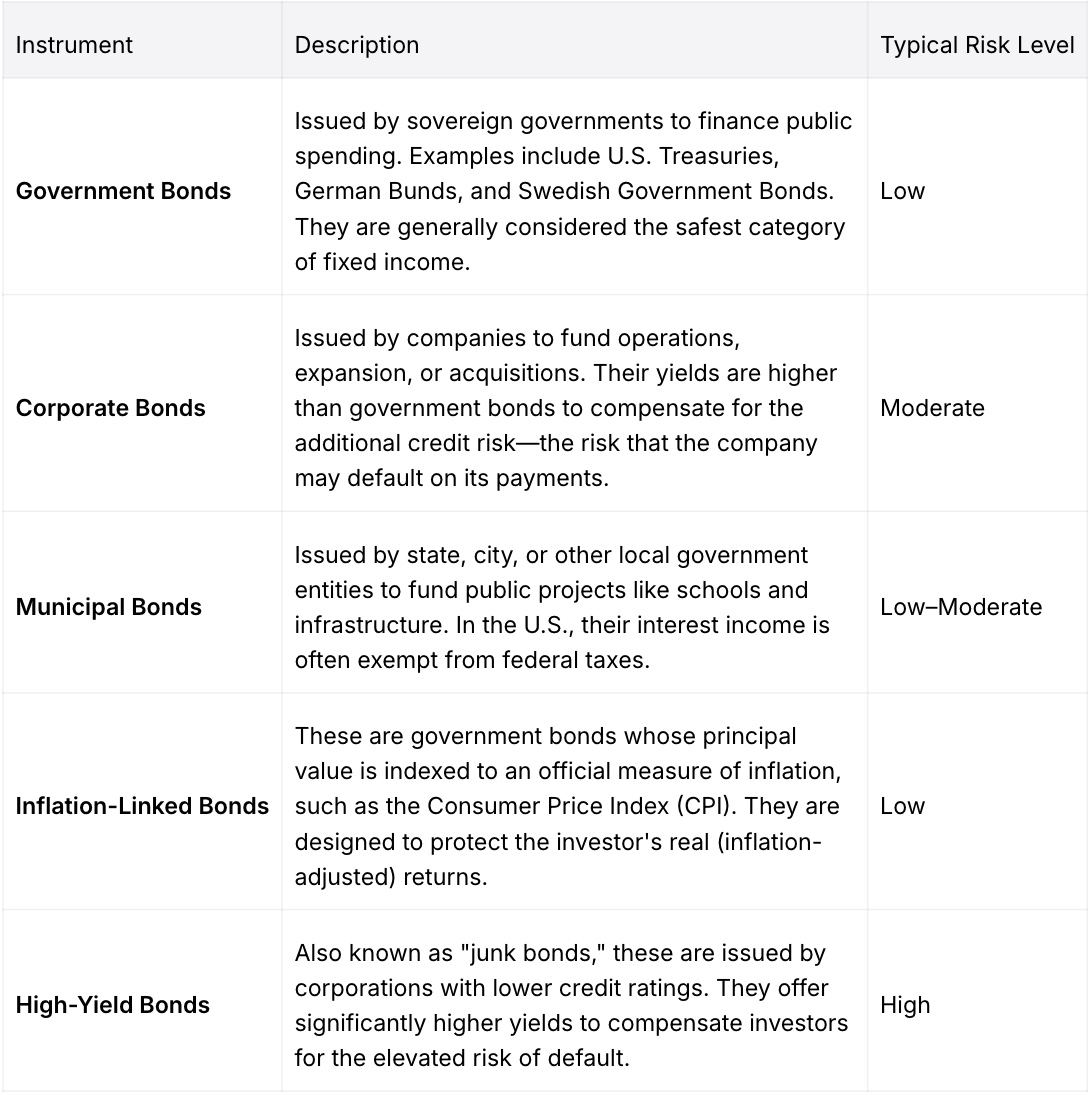

Major Types of Fixed-Income Investments

The fixed-income market is vast and diverse, offering a wide range of securities that cater to different risk appetites and investment objectives. A structured understanding of the major types is critical for effective portfolio allocation.

Global Bond Markets and Economic Signals

The global bond market serves as one of the most powerful barometers of economic health. Bond yields are a direct reflection of investor expectations for future inflation, economic growth, and central bank policy. Financial analysts and policymakers scrutinize yield movements for signals about the direction of the economy.

Central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and Sweden's Riksbank, are the primary drivers of interest-rate policy. Their decisions directly influence the yields on government bonds, which in turn serve as a benchmark for the entire fixed-income market. When the bond market's expectations diverge from a central bank's stated policy, it can signal a lack of confidence in the economic outlook.

One of the most widely watched economic signals is the inversion of the yield curve. This occurs when the yields on short-term government bonds rise above those of long-term bonds. Historically, a yield curve inversion has been a highly reliable predictor of an upcoming economic recession, as it suggests that investors expect economic weakness and lower interest rates in the future.

Benefits and Risks of Fixed-Income Investing

A balanced analysis of fixed income requires weighing its clear benefits against its inherent risks.

Benefits of Fixed Income

- Stability: Fixed-income securities exhibit significantly lower price volatility compared to equities, providing a stabilizing anchor in a diversified portfolio.

- Income: The predictable nature of coupon payments provides a reliable stream of cash flow, which is particularly valuable for retirees and other income-focused investors.

- Diversification: The price of high-quality bonds often moves in the opposite direction of stocks during periods of market stress, providing a powerful diversification benefit.

- Capital Preservation: During economic downturns or equity market crashes, government bonds are often seen as a "safe haven" asset, helping to preserve capital.

Risks to Be Aware Of

- Interest-Rate Risk: This is the primary risk for fixed-income investors. As detailed earlier, when interest rates rise, the market value of existing bonds falls.

- Credit Risk (or Default Risk): This is the risk that the bond issuer will be unable to make its promised interest payments or repay the principal at maturity.

- Inflation Risk: If the rate of inflation rises above the bond's yield, the investor's real return will be negative, eroding their purchasing power.

- Liquidity Risk: Some bonds, particularly those issued by smaller entities or traded infrequently, can be difficult to sell quickly without accepting a significant discount to their market price.

Active investment managers employ sophisticated strategies, such as duration analysis and credit diversification, to mitigate these risks and optimize portfolio returns.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Is fixed income a risk-free investment?

No investment is entirely risk-free. While generally safer than equities, fixed-income securities carry risks, most notably interest-rate risk, credit risk, and inflation risk.

2. Why do investors use fixed-income assets?

Investors use fixed income to balance the growth potential of assets like stocks with the need for predictable income, capital preservation, and portfolio stability.

3. What is the biggest factor affecting bond prices?

Movements in prevailing interest rates are the most significant factor affecting bond prices. The credit quality of the issuer is also a critical determinant of a bond's value.

4. How much fixed income should be in a portfolio?

The appropriate allocation depends on an individual's risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals. A traditional "balanced" portfolio often holds between 30% and 60% in fixed-income assets.